BOOK REVIEW: The Memory Keeper’s Daughter by Kim Edwards

On a cold winter’s night in 1964, Norah Henry goes into labour. Unable to reach the hospital in time, her husband David, an orthopedic surgeon, and his nurse Caroline, assist Norah with the delivery. Paul, the couple’s healthy baby boy, is born quickly and it is only while telling his wife the good news that David realizes something isn’t right. Sedating his wife with gas, Paul’s twin is born with Down’s syndrome, a little girl whom David names Phoebe.

On a cold winter’s night in 1964, Norah Henry goes into labour. Unable to reach the hospital in time, her husband David, an orthopedic surgeon, and his nurse Caroline, assist Norah with the delivery. Paul, the couple’s healthy baby boy, is born quickly and it is only while telling his wife the good news that David realizes something isn’t right. Sedating his wife with gas, Paul’s twin is born with Down’s syndrome, a little girl whom David names Phoebe.

Passing the child to his nurse, he instructs her to take the child to an institution and, reluctantly, Caroline agrees. When Norah awakes, David tells her that their little girl died as she was born. Miles away, Caroline finds herself unable to leave the child in the miserable institution and makes a decision that will change her life – she walks out the door and leaves everything behind to start a new life with Phoebe.

Kim Edward’s first novel, The Memory Keeper’s Daughter, is not an easy novel to read. Filled with a haunting sadness, painful decisions and far-reaching consequences, the world inhabited by the Henrys is a melancholy place. Haunted by the choice he made, David Henry is physically there for his wife but emotionally unavailable. Unable to share her grief with a world expecting the delight in her son to cover-over the loss of her daughter, Norah careens through her days unable to cope. Many cities away, Caroline is faced with a world which would rather her daughter be hidden away, and finds herself unable to keep silent.

In her February 12, 2006 review in the Washington Post of Ayelet Waldman’s Love and Other Impossible Pursuits, Kim Edwards subtitles her review “How a woman mourning the death of her infant daughter finds her way back to life.” This could just as easily be applied as one of a variety of subtitles for The Memory Keeper’s Daughter. So much is encompassed in this amazing book that, only with reflection do subtleties begin to shimmer into focus.

The Memory Keeper’s Daughter must be read within the context of its setting. To our modern sensibilities, the immediate disposal, upon birth, of a child with Down’s syndrome is repellent. By treating his daughter with careless disregard, David causes ripples far exceeding his expectations. Some readers will find within The Memory Keeper’s Daughter a meditation on loss and grief, traveling the lonely road with Norah as she grapples with the loss of a child she never sees, and a marriage within which this child is never discussed. Those same readers will most likely find David an unsympathetic character, whose misery is little payment for the pain he causes so many.

Others will read The Memory Keeper’s Daughter as a commentary on love and hope, focusing on the relationship between Caroline and her adopted child Phoebe. For those readers, Caroline is a force for change and rights for her daughter, insisting the world see Phoebe as a person capable of learning and of ability.

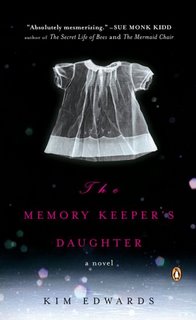

Despite some uneven writing, The Memory Keeper’s Daughter is astonishing in its power. Edwards does not allow readers to hold their preconceived notions for long. The translucent dress pictured on the cover illustrates Phoebe’s presence in her birth family, the unspoken words in David and Norah’s marriage, the haunting hole with Paul where his twin should be. The unseen Phoebe, the person she will never be, is at such odds with her reality that the effect is like a slap in the face, jolting the reader out of the too comfortable pathos and anger to see hints of the complex web Edwards has woven.

Kim Edwards is the author of the short-story collection The Secrets of a Fire King, which was shortlisted for the PEN/Hemingway Award. The Memory Keeper’s Daughter is her first novel.

This review was published at Curled Up with a Good Book.

ISBN10: 0143037145

ISBN13: 9780143037149

Publisher: Penguin Books

Publication Date: May 30, 2006

Binding: Trade Paperback

tags: books book reviews Kim Edwards The Memory Keeper’s Daughter Down’s syndrome